There is nothing wrong copying from another country/culture or from someone else, because copying is an important part of the learning process. However, what makes copying per se problematic or wrong is when one over copies blindly or fails to acknowledge the source(s) of the information or the event copied, making it seems as if the person copying is the originator of the ideas.

In academic world, for example, using another person’s ideas without duly recognizing the intellectual property of the owner/author, is a serious form of a dishonest behavior universally characterized as plagiarism, and it carries not only shame, fakeness, but more importantly, potential lawsuit, lifetime expulsion from a higher institution of learning and what have you. In short, copying from outside sources without proper acknowledgement or blindly over-copying, as fashionably found in many parts of Africa, often tends to draw a huge wedge between people and their true history or culture.

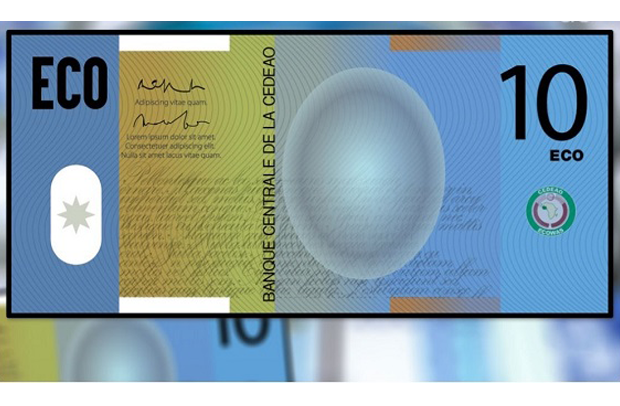

So, where are we going with this “copying, over-copying” lecture? In other words, what connection does the proposed single currency for West Africa countries have to do with “plagiarism” or “over-copying”? Well, listening attentively to many of the Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) leaders’ public and not-so-public pronouncements on their Eco single currency proposal, one is left with no doubt that the sub-regional leaders are copying directly from the European Union (EU) monetary policy playbook based on the single Euro currency concept.

As hinted earlier, copying is an essential component of human condition. Plus, it is amazing how seemingly unrelated events far and near across the globe tend to be interconnected directly/indirectly on so many levels that we may or may not even realize their (causal) relationships. Unquestionably, the EU’s creation has direct or indirect influence on the ECOWAS’ existence and subsequently the suggested adoption of West African unified monetary currency designated the Eco.

Distinctive to almost all copying/over-copying, comes with some gains as well as travails. In the case of ECOWAS and EU regarding single currency policy, the pattern remains the same. On paper or in theory, adopting a single currency to facilitate regional commerce and potential development of the West African sub-region sounds and appears mouth-watering, but desires and cold realities are polar apart.

Finding forward-thinking ways to help make ECOWAS more effective and relevant in the 21st century, West Africa must not include the creation of Eco or single currency as a sustainable safety net. Critical assessments, including accounts from a cadre of renowned monetary experts, all agree that the major challenge or big mistake the EU created along the way is the adoption of the single euro currency in 1999. Since the euro’s full adoption and its circulation in 2002, the EU has never been the same in terms of its operational efficiency, including the union’s sociopolitical cohesion among member states, as the Brexit bears eloquent testimony here.

The ECOWAS’ leaders may have good intentions with regard to their collective efforts to ensure the region has streamlined economic and monetary structures to promote successful interstate trading among member nations. But from a pragmatic point of view and as the EU leaders or bureaucrats have found out the hard way so far, no single currency can ever function in the absence of bureaucratic institutions set up to effectively absorb the constant shocks of the region’s (in our case ECOWAS zone) competing diverse interests and cultures.

Far from sounding as messenger of doom, the honest truth is that if the Europeans who are relatively more developed and have better infrastructures backed by “good geography”—natural harbors, navigable rivers, etc—that support viable economic development, are badly struggling with the single Euro currency, it is difficult for any realist to entertain false hope for the proposed Eco currency in West Africa.

Surely, the ECOWAS’ power brokers or member governments might have committed themselves into making sure the monetary system succeeds. Nonetheless, history teaches us that intergovernmental commitments at this level also entail some improbabilities and unpredicted events. Let’s wait until one member government/state encounters national disaster or internal turmoil that has potential to send negative socioeconomic reverberation throughout the entire sub-region. Most likely, citizens in some other member countries may start pressurizing their respective governments to withdrawal from the monetary union as the Brexit has amply demonstrated.

Also significant to know is that without Germany with its strong, robust economy that basically serves as de facto “cushion” for absorbing most of the rough economic blows against the relatively weaker member states such as Romania, Bulgaria, Greece, and so on, probably the Euro wouldn’t have endured this far. So, the question for the ECOWAS’ member states is: Which member nation will play reliable “shock absorber’ role for ECOWAS if the Eco is marred in financial crisis?

Needless to say, by attempting to adopt Eco-zone or single currency for the West African area, the ECOWAS member countries may be creating a “monster” that will definitely come back to haunt or torment the sub-region sooner than later. A concluding but serious question to consider here is, has the ECOWAS leaders learned any useful lesson from the EU’s ongoing challenges in terms of the fact that monetary and fiscal merger of nation-states is by nature political confederation?

Like all confederations of sovereign states, deep socio-cultural predicates such as linguistic barriers, tribal affiliations, religion, diverse traditions, in addition to ego or personality clashes that often play out among international union bureaucrats who are bent on upgrading their career profiles, can likely cause havoc to the steady pathways of the monetary union. Hopefully, my assessment of the adoption of the Eco single currency turns out to be wrong. Either way, time will tell, as the cliché goes.

By Bernard Asubonteng

Bernard Asubonteng is a US-based writer; he teaches university-level political science.