I hate lizards. A late uncle of mine, hating these reptiles too, spoke to one lizard once, as though it were human: “If you do not vamoose from here, I will chop off your head, and hang your body right on that wall to serve as deterrent to your friends!” Useless task, speaking to a lizard. But in doing so, this uncle of mine had with his unlearned mind (pardon this adjective—lawyers are peculiar) unraveled one crucial point in the web of criminal law—deterrence.

I hate murder—that is quite an unnecessary point to make, isn’t it? Because who doesn’t? In the spheres of morality, it lands atop any immorality list. To snatch life from a fellow human being; to cut a person’s essence short—within a matter of seconds. To deprive a person—filled with purpose, on a journey of existence—of said purpose, said existence, at whim, for whatever reasons—that ought remain the gravest of all ills man is capable of committing against man.

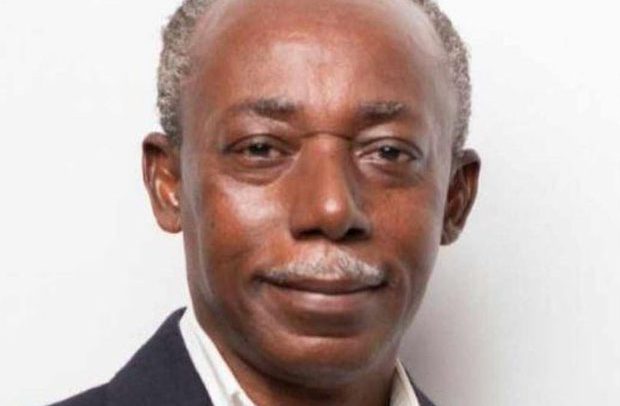

The Incomparable Dr. Benneh

An example of such man filled with such purpose, life, essence was Dr. Benneh. Dr. Benneh was a brilliant man—he held a world-class brain. It is often said, “A good lawyer is one who knows where to find the law”—indicating that lawyers do not necessarily have to—using this colloquial Ghanaian term—“chew” the law (have it all in their brains). Dr. Benneh chewed the law. The petit, skinny man, standing at about 5 ft. 2, would march straight into class always, never a book in hand, and commence his trademark impassioned lecturing.

Dr. Benneh was a simple man, as all extraordinarily brilliant people are. He made a bad case for international lawyers—with his Nokia 3310 phone (I presume), which would ring during class. He would bring this rickety phone close to his face, and painstakingly presson a button. And he, forgetting we are present perhaps, would start that same impassioned chat with whoever it is that called. And his VW Golf Mk 1 (Oh! that car)—one would think him poor.

For the life of me, I cannot stand picturing this large brain, housed by this small frame, bound hand and feet, in his pool of blood, wasting away—this Ghanaian world-class brain, wasting away; his purpose snatched. For whatever temporary reason, this force of nature, permanently has been snatched.

Anarchy

Yet, this is where we are—the egregious act of murder (assassination, mind you) already committed. Where do we go from here? The answer to this is already decided, per our track record as a society, the answer might just be: nowhere.

We should not be saying, “Hoh! The police can do nothing.” Yet, we find ourselves doing so—making jokes, the police jokes. When these jokes carry truth, what ensues is a gradual, quick decline of society into anarchy.

Each time there is a crime committed, with perpetrator escaped, the circle draws in closer—the circle of unsafety and fear. A vicious circle ensues: crime, perpetrator escaped, this encouraging more crimes. I am getting ahead of myself.

Crime & Punishment

Of all the branches of Law, the most retributive and coercive is Criminal Law. If Criminal Law were a teacher, it would be the one with most canes. This branch of Law has every reason to be that way, because the acts it safeguards against are so dire and far-reaching in their consequence, that all efforts must be made to discourage their happening. Take murder: what society would ours be, if murder was without the punishment of imprisonment? Think about it; think of all the people who wish you evil, people animalistic in temperament, hence capable, without inhibition, of committing heinous acts upon you. Think about those other people, seemingly incapable, yet in the presence of weak laws, surprisingly, too, capable of committing atrocious acts upon you. Imagine all these people left free, after committingwhatever it is they fancy, upon you. What society would it be? Now, think about your own self, if the inhibition of the law be absent, how far can you go? How deep can you fall—even from your highly held moral standards.

With every 50 pesewas groundnut you buy, you are bound to find at least one bad nut, no matter how well-packaged the nuts. Every society, even the most inherently peaceful (although, I’d argue there isn’t a thing as inherently peaceful society) is bound to have its fair share of headaches, criminals to disturb the peace.

Morality

You cannot trust my conscience; I cannot, yours. We cannot fully leave our lives into the hands of each other’s consciences. It is just not enough. And the law knows this. Hence punishment. A concept so closely attached to Criminal Law that the latter cannot be said to be in existence without the former. The law is a toothless bulldog, a venom-less snake, a white elephant, an armless parent threatening to cane a child, if it is unable to follow through with punishment. So then, how are you going to punish a murder if you cannot find him/her?

You are right (and not selfish) in saying, “We do not feel safe in our own homes,”whenever such acts are committed upon another. Because that is what it means to be in a society—the reality is that acts committed on person A, can easily be committed upon you and I (we are not selfish in contemplating this). Even I—Dr. Benneh’s student—having been taught Public International Law and International Trade Law by him in the University of Ghana School of Law; I, attempting to write a homage, all the while refusing to believe the news of his demise as true—find myself contemplating the personal too: it could be me—it could be you. Would we not be senseless, not demanding that the law and its institutions do their job?

The Joke

The problem is not with the law—it is with the institutions. Let us start with the police. This law enforcement agency is so crucial to the fabric of the law; hence, society; yet often dismissed, joked about, relegated to positions of un-importance in our minds, in our societies (strangely, not just Ghana, but worldwide. But this is a topic for another day). How do we intend to construct a functioning society if we cannot construct for ourselves a robust criminal justice system? How are we going to create this imperative criminal justice system if one of the first points of entry, one of the crucial law enforcement agencies—the police are perceived as a national joke?

I cannot do justice to the topic of police competence (or incompetence) if not done through a comparative lens. I would have to postpone my homage to the great Dr. Benneh at a better time (for me)—next week.

BY YAO AFRA YAO