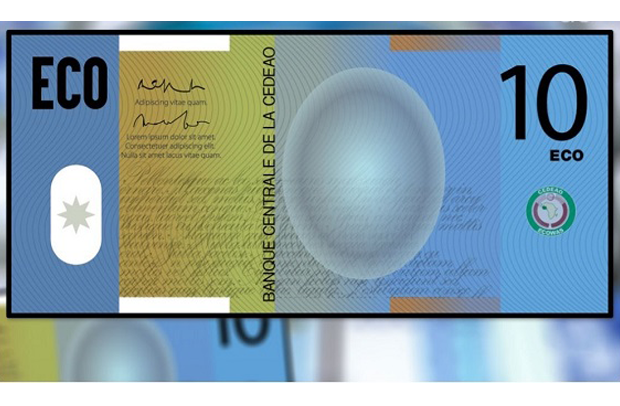

Nine days ago, Alassane Ouattara, President of Cote d’Ivoire, announced that the eight countries of the West African Monetary Union (WAMU) will discontinue the use of the CFA Franc and adopt the proposed, common currency of ECOWAS, the Eco.

There have been reports that WAMU countries will peg the Eco to the Euro.

From the standpoint of monetary policy, this makes no sense. The eight WAMU countries will be in a monetary union with seven other members of ECOWAS.

Whether the Eco will be pegged to the Euro or any currency will be determined by the Central Bank of ECOWAS that represents the interests of the 15 countries of ECOWAS. It cannot be unilaterally determined by any sub-group of countries within ECOWAS.

Therefore, either the WAMU countries accept the monetary policies and authority of the Central Bank of ECOWAS or they leave the Eco zone.

In a press statement on the decision of the WAMU countries to adopt the Eco, the government of Ghana urged the Member States of ECOWAS “… to work rapidly towards implementing the decisions of the Authorities of ECOWAS, including adopting a flexible exchange rate regime, instituting a federal system for the ECOWAS Central Bank, and other related agreed convergence criteria, to ensure that we achieve the single currency objectives of ECOWAS…”: http://www.presidency.gov.gh/index.php/briefing-room/press-releases/1463-declaration-by-the-government-of-the-republic-of-ghana-on-the-adoption-of-the-eco-by-uemoa

What is “a federal system for the ECOWAS Central Bank” in the Government of Ghana’s press statement? It is instructive to look at the organizational structure of European Central Bank (ECB).

The ECB, headquartered in Frankfurt (Germany), is the central bank of the 19 European Union countries which have adopted the euro.

Its main task is to define and implement monetary policy for the euro area and carry out a number of other tasks, including banking supervision. It is formally accountable to the European Parliament.

The Governing Council of the ECB is the main decision-making body of the ECB.

It consists of six members of an Executive Board (which includes the president, currently the former IMF boss, Christine Lagarde, and a vice-president) and the governors of the national central banks of the 19-euro area countries.

The six members of the Executive Board have permanent voting rights (i.e., have the right to vote at every meeting). The 19 governors of the national central banks do not have permanent voting rights. They take turns to vote on a monthly rotation.

In principle, the six members of the Executive Board – unlike the governors of the national central banks — do not represent any country.

Thus, they are expected to act in the interest of the Eurozone and their permanent voting rights is intended to ensure that this encompassing objective is achieved.

In this system, each national central bank is subordinate to the ECB and has no autonomy over monetary policy, banking supervision, payment systems, foreign exchange rules, etc.

The organizational structure of the ECB does not strike me as anything close to “a federal system”.

A federal system of central banks in a monetary union may be an arrangement that protects some monetary sovereignty or autonomy of the central bank of each country.

It may reflect a reluctance to lose monetary autonomy and act in the collective interest of the monetary union.

If this is what “a federal system for the ECOWAS Central Bank” is, then what is the point of having a monetary union? Is this Ghana’s or ECOWAS’ proposal? Or — based on the concept of fiscal federalism in which various sub-national levels of government have assigned powers to tax and spend — does monetary federalism, for example, mean that the ECOWAS central bank will have full control over monetary policy while each national central bank will have full control over banking supervision in its territory?

If the ECOWAS central bank will have a structure that is similar to the ECB’s structure, it must determine the allocation of voting rights among its 15 national banks.

In the Eurozone, countries are divided into groups according to the size of their economies and financial sectors.

The governors from countries ranked first to fifth – currently, Germany, France, Italy, Spain and the Netherlands – share four voting rights.

The other 14 countries share 11 voting rights.

A single currency is unlikely to work well if the countries in a currency union have, among others, restrictions on the movements of persons and goods and have very different macroeconomic conditions.

This is why, like the Maastricht criteria or convergence criteria of the Eurozone, a country must meet some macroeconomic criteria to join the ECOWAS monetary union.

These are a budget deficit of less than three percent of its GDP, an inflation rate of not more than 10 percent, and a debt burden of less than 70 percent of its GDP.

According to the Nigerian Finance Minister, Zainab Ahmed, only Togo is on track to meet these requirements.

But what if a country met these conditions when it joined the union but consistently failed to meet them in subsequent years? For several years, Greece posed this kind of challenge to the Eurozone.

In fact, Greece cooked its books (e.g., underreported its fiscal deficits and debt) in order to join the Eurozone in 2001.: https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-16834815.

A monetary union comes with challenges.

It is not surprising that the launch of the Eco has been postponed several times.

The challenges of the Eurozone offer food for thought.

The details, the devil, and all. The Eco in 2020? I doubt it!

Atsu Amegashie is a D&D Fellow at CDD-Ghana.

He is a Professor of Economics at the University of Guelph in Canada and a Fellow of the Center for Economic Studies and the Ifo Institute for Economic Research (CESifo) in Munich, Germany and the Tshepo Institute of Wilfrid Laurier University, Canada.

By: J. Atsu Amegashie