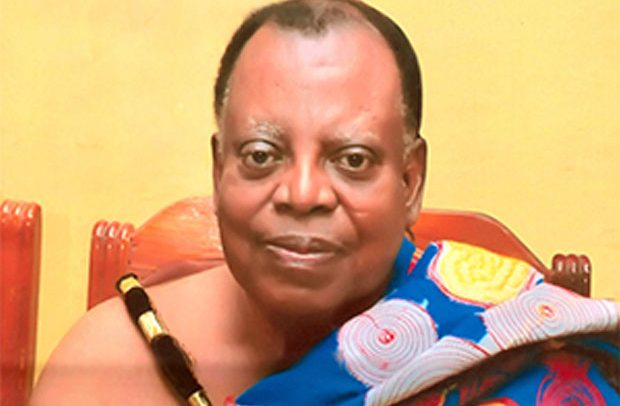

Nana Dr. S.K.B. Asante

Chairman of the Committee of Experts on the Constitution

- The Main Stages in the Evolution of the 1992 Constitution

- As a result of internal and external pressures for a return to constitutional rule, the National Commission for Democracy (NCD) established by the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC) carried out a series of public seminars and consultations with the aim of soliciting the views of individuals and organizations” on the nature, scope and content of the future constitutional order” between 5th July and 9th November 1990.

- This resulted in the publication of a NCD report entitled “Evolving a True Democracy” which was presented to the Government on 25th March 1991. A major finding in this report was a popular preference for a multi-party democratic system. This was the legacy of the late Mr. Justice Daniel Annan, the Chairman of NCD.

The report was accepted by the Government as “the embodiment of the aspirations of Ghanaians on the future constitutional order”.

- The next stage in the evolution of the 1992 Constitution was the establishment of the Committee of Experts in May 1991 to draw up and submit to the PNDC draft proposals for a draft Constitution. The Committee’s Report informed the deliberations of the Consultative Assembly which was charged with drafting the final Constitutional Document.

The Committee commenced its assignment on June 11 1991 and submitted its Report to the Government on 31st July 1991.

- The third stage was the inauguration of the Consultative Assembly on August 25, 1991. The Consultative Assembly comprised 260 members made up as follows: 117 persons elected by District, Municipal and Metropolitan Assemblies, 121 persons elected by identifiable bodies and 22 persons appointed by PNDC.

Two bodies, Ghana Bar Association and the National Union of Ghana Students refused to send a representative each to the Consultative Assembly on the ground that the structure of the membership would assure the predominance of PNDC sympathizers. The ultimate membership totaled 258.

The Consultative Assembly completed its assignment and handed over the draft Constitution to the PNDC on 11th March 1992.

- Attached to the draft Constitution were the Transitional Provisions containing the controversial immunity provisions in respect of certain acts and personalities in the PNDC regime. These provisions were not drafted and approved by the Consultative Assembly as a body. We have it on the authority of Professor Kwamema Ahwoi and Nana Atto Dadzie in their biography of Justice Daniel A. Annan that the Transitional Provisions were the subject of special negotiations between the PNDC Legal Team, headed by Justice Annan, and some leading Chairmen of the Committees of the Consultative Assembly. Obviously the Committee of Experts did not participate in the negotiation. I personally had returned to my UN job before the drafting of these Provisions.

- The Draft Constitution, together with the Transitional Provisions was subjected to a referendum on April 28, 1992 and was overwhelmingly approved by Ghanaians.

The Constitution was enacted on 8th May 1992 and gazetted on 15th May 1992. It came into force on 7th January 1993.

In this lecture, I will focus on the work of the Committee of Experts, pointing out those areas where the Consultative Assembly departed from the Committee’s proposals and leave you to act as the jury. I will conclude with an overview of our constitutional experience over the past 25 years and the prospects for the future.

- The Mandate and Work of the Committee of Experts on the Constitution

The Committee of Experts was established by PNDC Law 252 (1991), with the following remit: “to draw up and submit to the PNDC Council, proposals for a draft constitution of Ghana”. Section 4 of the Law instructed the Committee to take the following documents into account in its deliberations:

- The Report of the National Commission for Democracy of 25th March 1991 on “Evolving a True Democracy”;

- the abrogated constitutions of Ghana of 1957, 1960, 1969, and 1979 and any other constitutions;

- such other matters relating to proposals for a draft Constitution as the PNDC may refer to it;

- any other matter which in the opinion of the Committee is reasonably related to the foregoing.

- Furthermore, the Committee’s proposals were to be informed by certain basic principles. Specifically, the primary objectives of the proposals were:

- Provide for an Executive President to be elected on the basis of universal adult suffrage;

- Provide for a Prime Minister who must command a majority in the National Assembly;

- Provide for a National Assembly to be elected on the basis of universal adult suffrage;

- Guarantee, protect and secure the enforcement of the enjoyment by every person in Ghana of fundamental human rights and freedoms, including freedom of speech, freedom from arbitrary arrest and detention, freedom of assembly and association including the freedom to form political parties, women’s rights, workers’ rights and the rights of the handicapped;

- Provide for a free and independent judiciary;

- Guarantee the freedom and independence of the media;

- Provide for directive principles of state policy that shall ensure participatory democracy and the sound management of the national economy;

- Provide for a decentralized system of national administration based on a non-partisan District Assembly system with development as its objective and including revenue sharing clauses, and

- Reflect a commitment to equal and balanced development of all parts of Ghana, particularly, in the allocation of national resources and in the distribution of the national wealth.

- It is to be noted that the Committee was mandated to formulate constitutional proposals based on the foregoing core principles. These principles, in my view, were consistent with the fundamental tenets of a liberal constitutional order. Committed constitutional democrats may have honest differences over the institutional efficacy of the structures based on some of these principles, but I did not find that any of these principles was repugnant to a liberal constitutional order.

- The Committee operated under severe time constraints. We had barely two months to complete our assignment. Full membership was appointed in May 1991 and we commenced our deliberations on June 11, 1991 and produced our Report on July 31, 1991.

- The general environment in the country for the Committee’s work was uncongenial. A prolonged period of operating without a constitution unfortunately generated suspicion about the substance and outcome of our assignment. This contrasted sharply with the goodwill and support of the United Nations toward this exercise. The Ghana Bar Association which had boycotted the Consultative Assembly would not accord to me the courtesy of a hearing at its conference to discuss the proposals of the Committee. I was actually booed by “the students of my students!”

- The Challenges Posed by the Transition From a Military-Led Regime to a Civilian Constitutional Regime

- We had to contend with the existence of some skepticism in the higher circles of the PNDC regime about the viability of multi-party democracy.

- There was the strong feeling that all the institutions established during the regime should not be swept away on the inauguration of a constitutional regime. PNDC saw itself not simply as a military regime but as the precursor of participatory democracy and that its legacy to the foundation of grassroots democracy committed to the principles of integrity and accountability should be preserved (e.g. District Assemblies and Public Tribunals).

- There was some concern about the fate and role of the military in a constitutional regime.

- In the general public, particularly among the professional classes, there was a pervasive suspicion about the true intentions of the PNDC. The Committee was perceived as collaborators in some diabolical conspiracy to construct a spurious constitution to the detriment of the nation.

- Many of my friends and acquaintances told me that they would have advised me against undertaking the constitutional assignment if I had consulted them. So while the United Nations sent me off to my mission as a gallant standard bearer of constitutionalism to my country, the general public in Ghana was not enthusiastic about my assignment.

My own view was that PNDC’s offer of a programme of return to constitutional rule should be grabbed, particularly having regard to the basic constitutional principles enunciated in PNDC Law 252 which clearly committed the Government to a liberal constitutional order.

I conceded to my friend (Prof. Adu Boahen) that PNDC had not involved the general public or the prospective political actors in the drawing up of the agenda for evolving the Constitution, and to some leading members of the Bar – that the Bar was patently underrepresented in the Consultative Assembly (CA). But I argued that those limitations would pale into insignificance in the process of executing the agenda, because that process would generate its own momentum. While recognizing that PNDC had exploited its incumbency advantage, the inauguration of a liberal constitutional order would eventually set the country on a constitutional democratic track. As it turned out, although the Ghana Bar Association as a body ultimately did not participate in the Consultative Assembly, there were as many as 32 lawyers from other organizations and the Legal and Drafting Committee of the Consultative Assembly was chaired by the eminent jurist, Mr. Justice S.A. Brobbey.

The Consultative Assembly itself objected to our participation in their deliberations. Afari Gyan captured the plight of the Committee in the following dedication in his book: “To members of the Committee of Experts, who braved recriminations and personal abuse to do their work with dedication and conscience.”[2] Two members of our Committee were however invited by the Consultative Assembly to assist with the drafting of the final document.

The most charitable view of our predicament was that after a ten year break from constitutional rule, our Report uncorked all the pent-up feelings in the general public and afforded Ghanaians the first real opportunity to freely debate constitutional proposals, and we were obviously an easier target than the PNDC.

The Committee also had strenuously and successfully insisted that its Report should be presented to the Consultative Assembly without any comment or adjustment by PNDC. The price of independence was loneliness. We fielded all the ferocious criticisms alone.

In the end, I have no doubt that our role gave impetus to the constitutional exercise and paved the way to a lively and productive debate in the Consultative Assembly.

- The Committee was composed of the following:

Dr. S.K.B. Asante – Chairman

Osagyefo Oseadeeyo Dr. Agyeman-Badu – Omanhene of Dormaa, Member

Mrs. Justice Annie Jiagge–Retired Justice of the Court of Appeal, Member

Mr. L.J. Chinery-Hesse –Former Chief Parliamentary Draftsman AG’s Department, Member

Mr. Ebo Bentsi-Enchill –Ghana Bar, Member

Dr. K. Afari- Gyan –Lecturer in Political Science, University of Ghana, Member

Dr. Charles D. Jebuni –Lecturer in Economics, University of Ghana, Member

Dr. E.V. O. Dankwa –Senior Lecturer in Law, University of Ghana, Member

Mrs. S. Ofori-Boateng –Director of Legal Drafting AG’s Dept., Member/Secretary

There were also volunteers like Prof. Maxwell Owusu of the University of Michigan and two able research assistants, one of whom, Dr. Benjamin Kumbuor, became Minister of Interior and Attorney-General. We consulted with experts and personalities in public life, past and present and relied on the materials mentioned in the enabling legislation which included the constitutions of other countries and memoranda from individuals such as Prof. Paul Ansah’s memorandum on the Media Commission and Dr. Seth Twum’s memorandum on Human Rights and the Judiciary. We consulted with Dr. Alex Quaison-Sackey and Kwamena Ahwoi on a rotational system for head of state, using traditional leaders, and on decentralization and local government, respectively. Prof. Maxwell Owusu gave a fascinating paper on Media Freedom and Mr. Ansah-Asare also assisted with research.

- The report was not transmitted to PNDC for review before submission to the Consultative Assembly and the public. It was issued as the definitive Report of the Committee without amendment by or comment from any authority. As indicated above, the price of independence, however, was loneliness. We fielded the criticisms alone. CONTINUE NEXT WEEK

- The Organization of the Committee’s Work

As to the organization of work, we delineated some seventeen (17) areas for purposes of general discussion and formulation as follows:

- The Executive

- The Council of State

- The Legislature

- Directive Principles of State policy

- Fundamental Human Rights and Freedoms

- Freedom and independence of the Media

- Representation of the People Majoritarian or Consensus Democracy

- Political Parties

- The Judiciary

- Administration of Land

- Decentralization and Local Government

- Chieftaincy

- Enforcement of the Constitution

- Economic and Financial Order

- Public Administration

- Amendment Procedure; and

- Citizenship

Individual members were assigned the task of preparing proposals covering specific, identified areas. The proposals formulated were subjected to a general critique at the plenary session. Thereafter, the proposals were finalized. This involved two steps, namely

- A discussion of the relevant issues, the resulting proposals and the rationale for these proposals and

- A precise formulation or drafting of the proposals that would provide the basis of the key constitutional provisions.

- THE SUBSTANCE OF THE REPORT

Within the extremely limited time or barely two months, the Committee produced a report entitled the “Report of the Committee of Experts (Constitution) on proposals for a draft Constitution of Ghana”, covering the above-mentioned subjects. The Committee’s proposals were substantially adopted by the Consultative Assembly. However, the Consultative Assembly departed from a significant number of the Committee’s proposals in such areas as the structure of the Executive, the structure and functions of the Council of State, representation of the people, Chieftaincy and local government.

- IMPACT OF THE WORK OF THE COMMITTEE OF EXPERTS

Although the Consultative Assembly departed from a significant number of the proposals submitted by the Committee of Experts, the Committee’s Report informed the deliberations of the Consultative Assembly which ultimately endorsed the bulk of the Committee’s proposals. The Committee’s work generated a lively national debate on the structure and content of the future Constitution for the country and intensified the momentum for the transition to constitutional rule. Finally the Report of the Committee has proved to be the main document relied on by the Supreme Court in interpreting the Constitution since it came into force some 25 years ago.

- OVERVIEW AND PROSPECTS FOR THE FUTURE

With all the shortcomings of our Constitution, we can boast of a functional, liberal constitutional order based on a multi-party system which assures us, inter alia, peace, law and order, an independent judiciary, fundamental human rights and freedoms, freedom of the media, universal adult suffrage, modest parliamentary oversight over the Executive, a robust version of judicial review and a reasonable measure of decentralization.

For the past 25 years, we have successfully operated a constitutional democracy under which there has been a peaceful transfer of power from one party to another on three occasions through the ballot box. Ghana has been acclaimed as a haven of constitutionalism, peace and stability in a turbulent region and as a beacon of democracy for Africa.

Ghana has survived as a national entity and a fully integrated and functional state for sixty years.

However, there is no room for complacency. The successful conduct of six elections without a major outbreak of conflict is to be appreciated. But the conduct of peaceful elections does not exhaust the essence of democracy.

If we adhere to these fundamental tenets of national integration and ensure even development of all parts of Ghana and opportunities to the people to participate in decision making at every level of national life and in government, we would be able to point our form of governance as a model to the rest of Africa.

[1] Report of the Committee of Experts (Constitution) on proposals for a draft Constitution of Ghana. Ghana Publishing Corporation 1991

[2] The Making of the Fourth Republican Constitution of Ghana, Friedrich Ebert Foundation 1995, p iii.

By Nana Dr. S.K.B. Asante