Flt. Lt. Jerry Rawlings twice seized power in Ghana but returned the country to democratic control.

After his first coup attempt, he was sentenced to death but he escaped to overthrow the country’s military government.

Two years later Rawlings removed a democratically elected head of state but then successfully stood for election himself.

Initially a committed socialist, he introduced free-market reforms and made his country a major player in UN peacekeeping missions.

Jerry John Rawlings was born in Accra on June 22, 1947, the son of a Scottish farmer and a Ghanaian mother.

He attended Achimota Secondary School, where he excelled on the polo pitch and was described by fellow pupils as outspoken and rebellious.

In 1968, he enrolled in the military academy at Teshie, near Accra, and was later sent to a flight training school.

Commissioned as a second lieutenant, he gained his wings and joined the elite Fourth Squadron of jet fighters based in Accra.

By the time Rawlings had been promoted to flight lieutenant in 1978, he had become politically active.

Ghana, the first African country to become independent from Britain, was suffering food shortages, inflation and economic stagnation.

Rawlings vented his anger at what he saw as the indiscipline, corruption and mismanagement of the military regime.

When a ban on political parties was lifted in 1979, Rawlings won wide popularity as a prominent critic of the government, calling on it to do more to help the poor.

Buoyed by this support, Rawlings launched his coup attempt in May 1979. It failed and he was arrested and sentenced to death.

He escaped from jail thanks to the help of junior officers and other ranks and overthrew the country’s military leader, Gen Fred Akuffo.

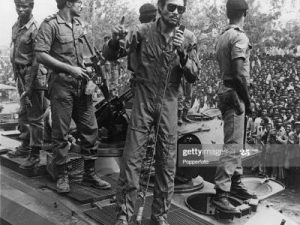

Rawlings took the reins of government as leader of the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC), prompting the memorable headline in one British newspaper: “Half-Scottish polo player takes over in Ghana”.

The AFRC had vowed to hold Ghana’s former leaders to account, and Akuffo and other military leaders were executed.

Judges killed

Rawlings launched what he termed a “housekeeping exercise” to rid Ghana of what the AFRC perceived to be the corrupt practices of the military regime.

A number of senior judges and military officers were killed during this period.

But, far from clinging to his newly gained power, Rawlings initiated an election within four months of his coup. The newly formed People’s National Party, led by Hilla Limann, came to power.

Austerity

However, Limann was seen by many as a mere stooge for Rawlings and his failure to turn Ghana’s economy round soon brought his time in office to an end.

With foreign debt spiralling and inflation at more than 140%, public discontent began to spill over into unrest.

And, on December 31, 1981, Rawlings intervened for a second time, staging a coup that brought a new government, the Provisional National Defence Council (PNDC), to power. The PNDC, with Rawlings at its head, sought to transform Ghana into a Marxist state.

It introduced workers’ councils to oversee the country’s factories, workers’ defence committees sprung up in every community, and Rawlings turned to the Soviet Union for support.

But just two years into its communist experiment, Ghana abandoned it.

Perhaps sensing that the Soviet bloc was on the verge of collapse, Rawlings took steps to embrace the free market.

He devalued the currency, stopped hiring workers for state enterprises and privatised Ghana’s nationalised industries, including its vitally important coffee and cocoa plantations.

Landslide election victory

But, although this transformation pleased the West and the International Monetary Fund, the austerity that came in its wake fomented domestic unrest.

Between 1983 and 1987, Rawlings survived five coup attempts. A government clampdown, in which opposition leaders were arrested and imprisoned, outraged human rights campaigners around the world.

The situation was made even worse when a million Ghanaians were expelled from neighbouring Nigeria.

But, by the early 1990s, his reforms had led the country towards a strong economic recovery and, in 1992, Rawlings won Ghana’s presidential election.

His landslide victory, with 58% of the vote, was judged fair by the Commonwealth and the Organisation of African Unity.

And, thanks mainly to the country’s new-found economic stability, he was re-elected in another landslide in 1996.

He boosted Ghana’s international image by contributing many of its troops to UN peacekeeping operations, most notably in Liberia, Sierra Leone, Lebanon and Iraq.

In 2001, his second term completed, Rawlings took an almost unprecedented step for an African leader and resigned from office.

Though he called for “positive defiance” against the government in 2002, an act for which he was questioned by police, Rawlings did nothing to secure a return to power.

In later years, Rawlings campaigned for African nations to have their international debts written off. And in 2010, he was named as the African Union envoy to Somalia.

Jerry Rawlings’ legacy is controversial and he divided opinion domestically and in the wider world.

His detractors accused him of torture, corruption and worse. To his supporters, he brought order, security and prosperity to Ghana.

Source:BBC