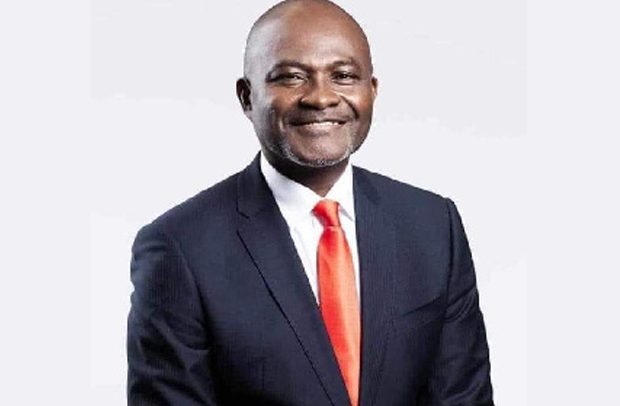

Kennedy Agyapong

The presidential campaign of Kennedy Agyapong has sprung from the fringes into the mainstream, making him a serious contender and catching many people off guard. What suddenly changed? And what comes next? Varied opinions, perspectives, and personalities have sought to either demystify his rising popularity or attack his qualifications to become President of the republic. They have made assertions that his low frustration tolerance, impulsive temperament, vulgar utterances, arrogance, and contemptuous disregard for those who disagree with him make him distinctly unsuitable for the highest office of the land.

Notwithstanding these varying opinions, one thing is clear: in moments of crises, opportunistic and populist leaders bully the silent majority into submission and use fear, intimidation, and manipulation to occupy the political space. Examples abound in the wake of the disastrous legacies of Jacob Zuma of South Africa and Jair Bolsonaro of Brazil.

Certainly, the global economic crisis unleashed by the Covid-19 pandemic has presented populist politicians such as Kennedy Agyapong with the opportunity to project themselves as Messiahs. However, as was the case in Jacob Zuma’s South Africa, while populist politicians are often crafty at using their narcissistic impulses to connect with the discontented masses for their own self-aggrandizement, their inherent flaws become readily apparent once they assume office and leave behind a legacy of shattered economies and weakened democratic institutions. Today, thanks to the populism of Jacob Zuman and his henchmen, South African, which has the most sophisticated and advanced economy on the entire African continent, is in a state of unprecedented decline.

The legacy of Jacob Zuma’s reckless rhetoric includes the formation of the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) whose proclivity to violence, disruption and sabotage is unparalleled in the history of democratic South Africa. The South African experience could be replicated in Ghana if Kennedy Agyapong’s rhetoric prevails because history does not only give us the tools to analyze and explain problems in the past, it provides us a crucial perspective for understanding current and future problems.

The purpose of this article is to call out Kennedy Agyapong’s populist impulses as potential fodder for both anarchism and fascism in Ghana. Words are potent forces for all causes, good or bad. And as Dorothy Neville eloquently said, the “real art of conversation is not only to say the right thing at the right place, but to leave unsaid the wrong thing at the tempting moment.” If Kennedy Agyapong’s bombastic rhetoric prevails, like Jacob Zuma, he can incite a crusade that can quickly morph into an intolerant and anti-state movement, which will ultimately undermine our pluralistic state and stability.

Kennedy Agyapong is an unusual politician: he is both a successful businessman and a vociferous lawmaker. In business, he has leveraged his shrewdness and access to power to build a successful empire. For example, he was an influential member of former president Kufour’s government. He is the current Board Chair of Ghana Gas, a position he occupies from President Akufo-Addo’s appointment.

Notwithstanding his access to power, influence, and resources, he projects himself as nonconformist, a maverick and not part of the elite. He also portrays himself as a pragmatic politician who has the requisite courage to uproot corruption, fix our broken systems and turn the economy around. In so doing, Kennedy Agyapong has set out to occupy the crowded space of would-be Messiahs who believe they can rescue Ghana from the global economic crisis and finally deliver the democratic promise of providing prosperity for all.

Unsurprisingly, Kennedy Agyapong’s prescriptions for turning the economy around and eradicating corruption are so vague that everyone seems to agree with him, yet nobody knows how he will get them done or even get parliament to ratify them.

Nonetheless, when challenged, he uses the populist playbook of deflecting accountability by attacking his critics and casting them as enemies of the people. Drawing from the playbook of Jacob Zuma, Robert Mugabe, and Hugo Chavez, he sees politics as a war between good and evil. Hence his penchant to demonize his rivals.

Interestingly, it is his unorthodox politics that is appealing to people who are deeply dissatisfied with the status quo and with rising poverty. These people are yearning for a radical change because state institutions have either lost their legitimacy or public confidence in their ability to deliver good governance.

He has therefore tapped into the rising discontent to demand allegiance to his-all-powerful, enigmatic personality. He stokes the enthusiasm of his followers by identifying with their cause and inciting suspicion of those who question his rhetoric.

The inherent danger in his populism is that even if he can change the status quo and weed out corruption as he has promised, which of course is unlikely, his “us” versus “them” approach will always carry the seeds of intolerance, hate, division, and authoritarianism, which will ultimately set the grounds for anarchism and fascism.

Throughout history, anarchist, demagogues, fascist, and their henchmen who claimed privileged knowledge and skills to solve society’s problems have ended up crushing the very people they claim to represent. When populists portray their opponents as inferior, idiotic and incompetent, it is only a matter of time before they trample on their rights and anyone who disagrees with their agenda — thereby undermining pluralism and rule of law.

The current discontent in the country is not unique to Ghana but stems from the apparent failure of democracies to close the disparity between the rich and the poor. The situation has been compounded by the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic. As a result, democracy, which as a social contract derives its legitimacy from the promise of improving the lives of all the people, is failing to deliver. Thus, even in advanced democracies such as the United States, Italy, Sweden, etc., populist mobilization has undermined democracy and pluralism.

Kennedy Agyapong’s populism is gaining ground because he promises renewal and a shift in focus from meeting the needs of the powerful elite to representing the people. However, given his personality traits, and inability to respond to constructive criticism, he may choose to ignore key customary practices of good governance such as proper consultation and respect for independence of institutions once in power, which will ultimately undermine democracy and rule of law.

Win or lose, Kennedy Agyapong has taken populism to new heights in Ghana. And if democratic governments appear unresponsive to public opinion and demands, then, just like in the United States, populism in Ghana is likely to become entrenched. The country may enter a dark era of serial populism, fostering the environment for anarchy and fascism.

By Kwame Attakora Abrefah, Esquire