WE HAVE been talking about clericalism which has created a division between the clergy and laity. In last week’s edition, we quoted Professor Emmanuel Asante as stating that in the secular Greek, laos (laity) was used in reference to the population of city-states. In biblical Greek, Laos was intended to mean the whole people – that is, a people who are sacred, as distinct from those who are not. Laos then was an inclusive word, denoting all the people of God.

Touching on cleros, Asante quotes Robinson and makes the point that, though two words, cleros (clergy) and Laos (laity), appear in the New Testament (NT), strange to say, they denote the same people, not different people. He further quotes Lightfoot as writing that “the only priest under the Gospel, designated as such in the N.T., are the saints, the members of the Christian brotherhood.”

He concludes by stating that “all Christians are God’s laity and all are God’s clergy.” Papesh claims that the first thousand or so years of Christianity witnessed the establishment of a culture of clergy separated from the laity. The next thousand years defined and refined the separation, right down to our day. Though the clerical culture in our time is shaken and fading in many respects, the material, relational, and ideational world that shaped the clerus during the last thousand years is alive and well.

One question we wish to ask is: can the culture of clericalism be brought to an end or eliminated from Christianity to promote accountability in local churches and practicalise the doctrine of the priesthood of all believers? Are there certain intentional practices that are upheld by the clergy to firmly maintain, perpetuate and promote clericalism in the church?

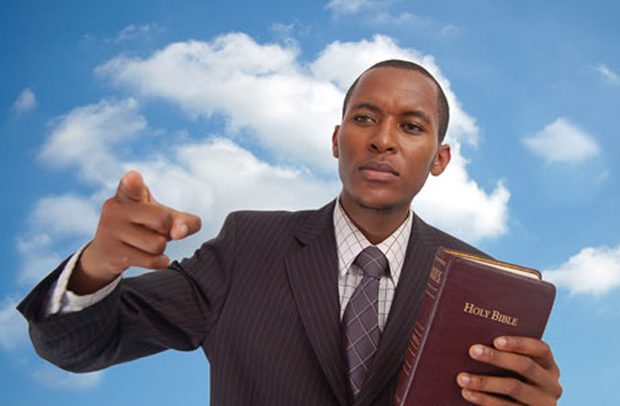

Wilson seems to agree that certain practices clearly help to maintain clericalism in Christianity. He points out that the arrival of a clergy group frequently comes to expression in the form of external symbols such as distinctive dress, titles, and forms of address, and associations with symbolic objects. And then there are perks accorded to the clergy.

Some of the titles used by the clergy to split the church and for them to appear special, superior and important, according to Alexander Strauch, include: reverend, archbishop, cardinal, pope, primate, metropolitan, canon and curate. Kenneth Hagin also mentions others as bishop and apostle. Of course, there are others. These are referred to as ecclesiastical titles.

These titles themselves, in the words of Wilson, stir up a whole set of attitudes and behaviours in their respective laity. Darrly M. Erkel notes that the use of the titles helps to promote an elitist attitude and authoritarian forms of church leadership, detract from the glory that rightfully belongs to Christ alone.

He further states that the use if the titles also perpetuates the clergy-laity dichotomy of the church of God, making the specially-ordained ministers superior to the generally ordained baptised believers. This influences the latter to shirk their responsibility in participating in the one ministry of Christ, the Lord.

Stephane Joulain says that clericalism is embedded in a specific social context and is perpetuated by various forms of systematic resistance. According to him, clericalism is also maintained by corporate dynamics, including a culture of secrecy, a lack of accountability and transparency, and the inability of many ministers to envision the need for a deep reform.

That apostles, bishops and prophets have been made to appear superior to Christian believers they oversee is an undeniable fact. A statement made in a newspaper article authored by Owusu-Ansah gives credence to this fact. Quoting the current Anglican Bishop of Kumasi, Rt. Reverend Oscar Christian Amoah, Owusu-Ansah writes, “He pledged to rule with truth, justice and charity.”

According to Owusu-Ansah, he wrote the article after participating in the programme tagged, “The Great Enthronement Thanksgiving” of Bishop Oscar Christian Amoah. The Anglican Bishop’s pledge to rule, obviously the laity, agrees with Daly’s observation that, “they rule over the church as if they were feudal lords in a feudal society.”

But are the ordained ministers supposed to lord it or rule over the churches entrusted to their care? The Lord Jesus Christ speaks concerning this in Matthew 20:25-26, “You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them, and those who are great exercise authority over them. Yet it shall not be so among you; but whoever desires to become great among you, let him be your servant.”

On this, Asante writes, “ministry is not about rule, neither Lordship nor the exercise of authority or power. It is about service and being a slave in the sense of being a servant.” Cosgrove also notes that this teaching of leading by serving continues to have an unfamiliar ring in an age that calls for us to do everything we can to climb to the top. The Bible teaches that to lead is to serve. We may recognise the truth of this concept and respond positively.

Clark G. Fobes asserts that unless we fully understand the biblical call of the priesthood of all believers, the church will remain stuck in the present, or romanticising about the past. A future recovery of lay empowerment for mission must start with a biblical foundation of the doctrine.

He continues that understanding the biblical call of the priesthood of all believers in the church requires understanding the roots of “priesthood” as it related to Israel, which the New Testament writers were also drawing from. Throughout the Old Testament, Israel is referred to as God’s chosen people from among the nations, called to make Yahweh’s name known to the surrounding peoples.

To be continued

By James Quansah

Jamesquansah@yahoo.com